AZ Alkmaar: The club where coaching goes against

convention

AZ Alkmaar made Dutch footballing history in April.

They became the first team from the Netherlands to win the UEFA Youth League, the under-19 age group’s Champions League equivalent.

AZ’s youngsters scored 14 goals and kept three clean sheets in their four single-leg knockout matches from play-off stage to the semi-finals, eliminating Eintracht Frankfurt (5-0), Barcelona (3-0), Real Madrid (4-0) and Sporting Lisbon (on penalties after a 2-2 draw), before beating Hajduk Split 5-0 in the final.

Last month, they played Boca Juniors Under-20s at the Argentine club’s iconic La Bombonera stadium in Buenos Aires for the Under-20 Intercontinental Cup, a Super Cup of sorts, after Boca won the Under-20 Copa Libertadores in July. AZ lost on penalties after a 1-1 draw in front of a crowd of over 37,000 with seven of their starting XI having played in that final against Hajduk.

And now, AZ’s next generation of academy talent have begun the defence of their Youth League crown in dominant fashion. Their 12-0 defeat of Lithuanian visitors Klaipedos on Tuesday is the biggest win in the competition’s history.

Paul Brandenburg, AZ’s academy director, told Sky Sports that “each generation is different, it is all about the talent and the individual. When we see talent, we are convinced that our programme will make sure that the talents will arise”.

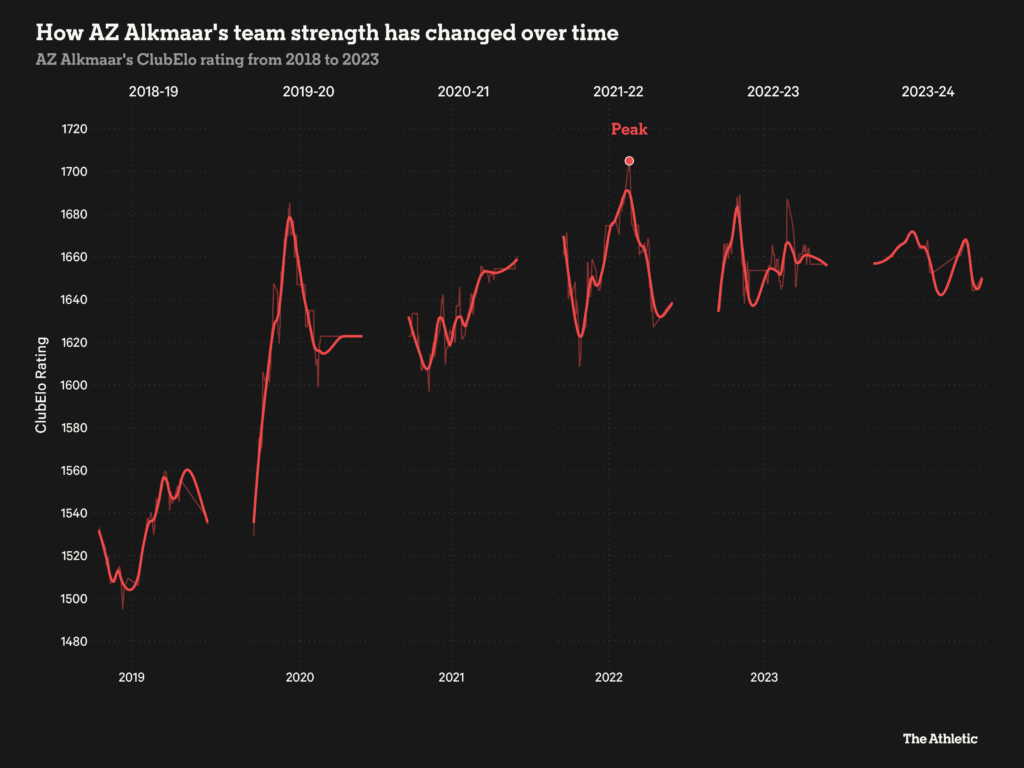

He was not speaking there about their ‘class of 2023’ but AZ’s first team, who were pushing Ajax for the Eredivisie title in the early spring of 2020. The clubs had identical records — 18 wins, two draws and five losses — when the pandemic hit that March, with the Dutch football season subsequently abandoned and voided the following month with no champions crowned and no relegations.

“It is really exciting to see how much we can achieve with players of our academy,” Brandenburg also said.

AZ continue to vindicate Brandenburg and top some of Europe’s biggest clubs for talent identification and development, even though they are on Amsterdam-based Ajax’s doorstep, with Alkmaar located just 40 kilometres (25 miles) to the north.

Their AFAS Stadium holds 19,400 people — less than half of Ajax’s Johan Cruyff Arena and their budget is a fraction of what Ajax, Feyenoord and PSV Eindhoven have to spend. But put those four clubs into their own mini-league from 2018-19, and AZ come out on top for wins and points in matches played among them.

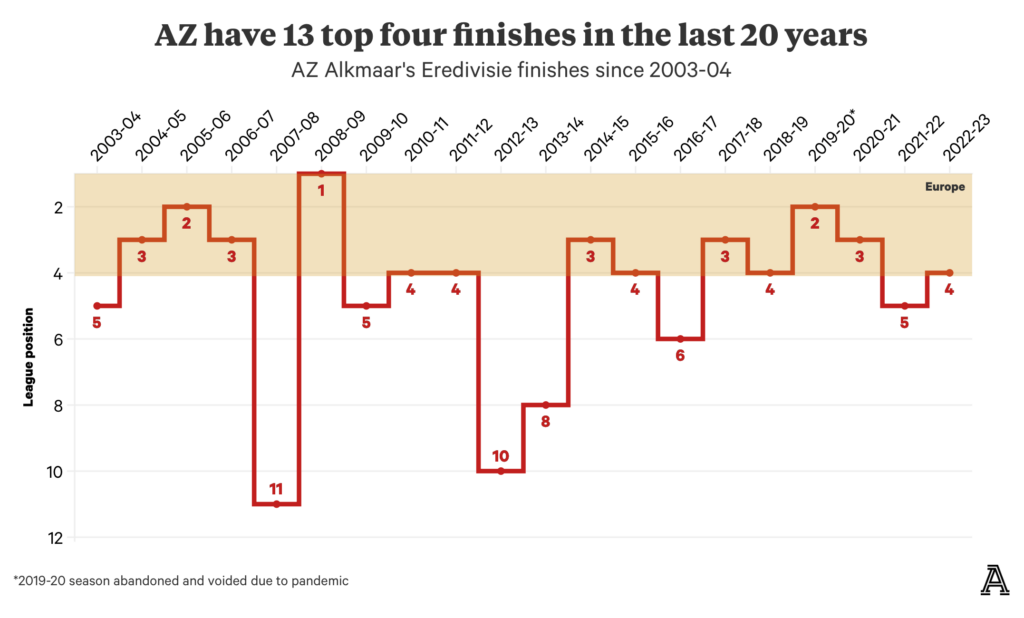

They have not won the Eredivisie since 2008-09, when Louis van Gaal was head coach, but have finished in the top four in nine of the 14 seasons since. They were Europa Conference League semi-finalists last season, too, beaten by winners West Ham United in a tie that was in doubt well into added time at the end of the second leg.

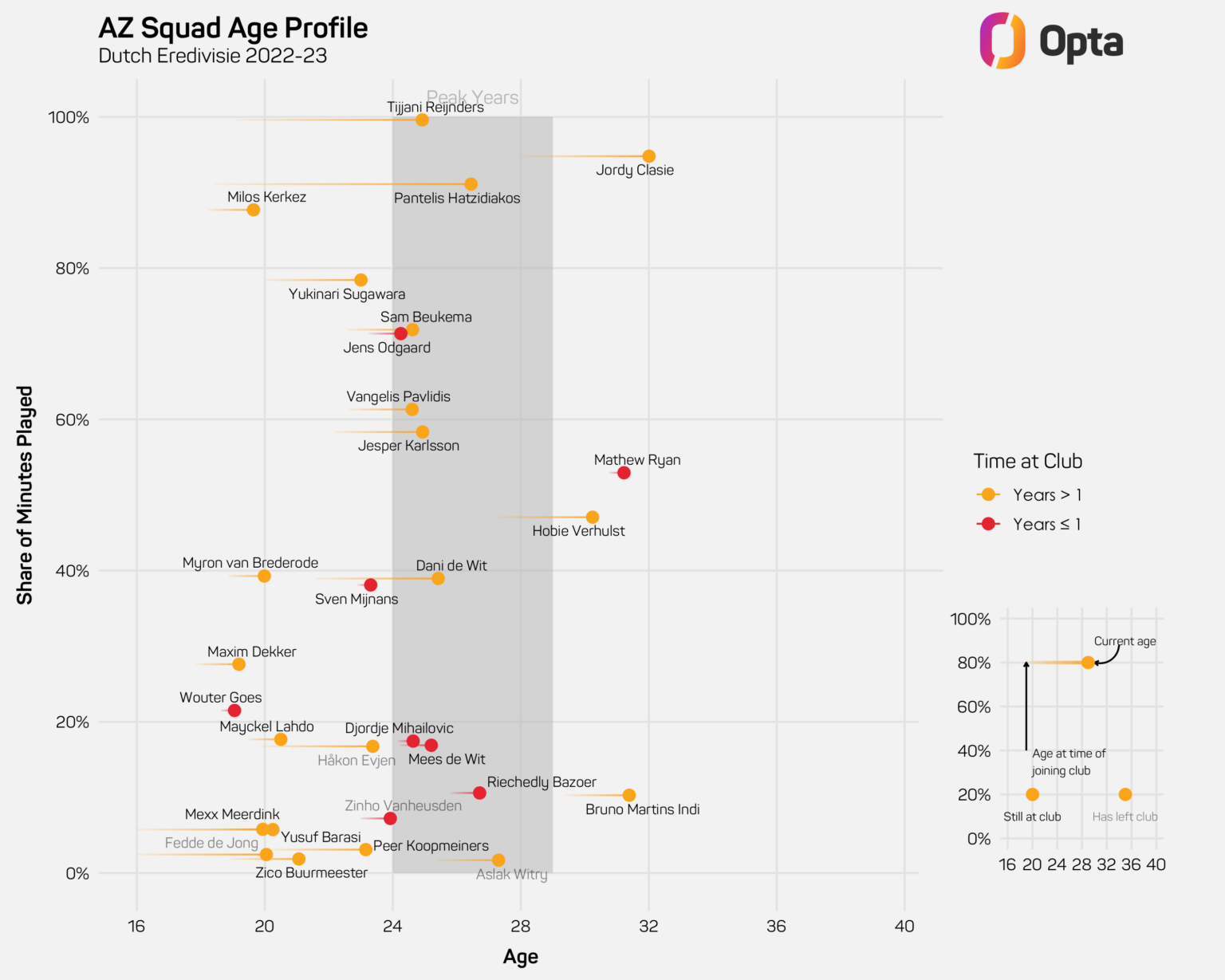

This season, after seven Eredivisie games, AZ are unbeaten and second, having outscored opponents 20 goals to three. It is their best start to the season since 1980-81, and comes after the summer sales of several key players — central midfielder Tijjani Reijnders, left-back Milos Kerkez and centre-back Pantelis Chatzidiakos, who all spent time in AZ’s academy at some level.

Jong AZ, their reserve team, which is made up of under-21 players, play in the Dutch second tier, the Eerste Divisie. Ajax, Utrecht and PSV also have Jong sides in this division. Last season, AZ’s kids finished higher than the other three for the first time.

Their continued success in developing both teams and individuals — notoriously difficult things to do; typically one happens at the expense of the other — are underpinned by a uniquely run academy that uses:

Neuroscience technology in player identification and development Integration of physical and technical data, and Billy ‘Moneyball’ Beane’s involvement Banning tactics until under-16s level, with a focus on holistic development Biobanding and contemporary approaches to coaching Planned disruptions to develop creative, problem-solving players Establishing and maintaining a pathway to first-team football. One of the biggest challenges for academy practitioners is to identify and develop footballers. The game is constantly evolving tactically, but it has also become technically faster, tougher, and physically more intense over the past decade.

Youth players have undergone physical testing for years and processes such as biobanding (grouping players based on physical maturity rather than chronological age) are commonplace in academies.

Biobanding is something AZ use too, but their adoption of neuroscience for player identification and development is relatively unique.

AZ work with BrainsFirst, a company from Amsterdam, which uses game-based assessments on tablets to test the brain skills of players, from the ages of 12 up. Eric Castien, the founder, explains that twice a season thousands of youth players in elite professional football academies play the NeurOlympics: gamified neuroscientific tasks that challenge various parts of their brain.

Neuroscientists Ilja Sligte and Andries van der Leij developed these games in 2013, aiming to reveal the building block of a player’s game intelligence. Players have to retrieve, remember, filter and distinguish information, to switch tasks, to recognise patterns and control impulses.

Now with a database of more than 200 elite-level players, BrainsFirst, enable clubs to improve recruitment decisions. “We give them a data-informed estimate whether the brains are, or will be, able to meet the requirements of modern football,” Castien says.

By 16, the “predictive value of the scores is enough to make better decisions” on the future cognitive capabilities of a player. There are “already some visible differences (for outliers) at 12 and 13 years old, but not predictive enough. Outliers at that age are already promising but the brain is too immature to reject talents based on that,” he adds.

What the company does not do is make 100 per cent claims about the probability of a player being good enough at an older age, but they can “lower the risk” of recruitment mistakes and it is another way that players who mature later on can shine through.

Castien calls cognitive data a piece of the “multifactorial puzzle” of modern football. “Clubs want evidence on the pitch, stories like AZ, with their oldest youth teams,” he says. All of AZ’s Youth League-winning squad were assessed by BrainsFirst. Castien adds that being at a high level cognitively is “essential, crucial to play elite football today, because it is more demanding for the human brain than 10 years ago”.

AZ are one of 37 clubs, Castien says, that use BrainsFirst. He is keen to bust the myth that footballers are stupid, that while some may not be academic high-achievers they do boast a “specific intelligence”, in terms of brain skills like attention speed and information processing, that are comparable with the levels of air traffic controllers in Germany. A significant strength of the software is not just that it can help predict who is more likely to succeed, but how they might do that.

By assessing how players collect and process information, what their attention and anticipation levels are like and how they recognise patterns and then execute actions, recommendations can be made on the position they might play, or how best to tweak tactics to maximise strengths and limit weaknesses. For instance, players who are not able to process lots of information quickly are best kept out of central spaces, where they will come under more pressure and have to make more well-considered decisions faster.

The European Club Association’s 2022 report on academies identified that only eight per cent of clubs were testing the IQ of players. AZ go way beyond simplistic IQ testing, and their approach to adopting new ideas is industry-leading.

“Until the under-16s, tactics is a forbidden word in our club,” Marijn Beuker, AZ’s former sport development director, told The Training Ground Guru podcast.

AZ split their footballing principles based on age group. Between under-11 and under-13, they prioritise skill acquisition, particularly movement patterns — in other words, letting players learn to play. From under-14 through to under-16, Beuker speaks of “game intelligence”, where they begin to teach principles and patterns.

“In the under-17s upwards, you have your principles to win games,” Beuker says. “Tactics are important at the end of the academy journey, when you have to win matches, but they are sometimes the opposite of creativity. We would rather win championships with the first team.” Instead, their coaching focuses on implicit teaching.

Sessions and practices are designed so that players learn through doing rather than having the coach tell them. Putting tennis balls in the hands of defenders, to stop them grabbing the shirts of opponents, is one example, as is cutting off the corners of the pitch to make the full-backs play more advanced.

They develop problem-solvers. Central midfielder Teun Koopmeiners (then 21), winger Calvin Stengs (20), full-back Owen Wijndal (19) and No 9 Myron Boadu (18) were four of AZ’s six most-played players in the 2019-20 season. All four were academy graduates and left, in moves to Atalanta, Nice, Ajax and Monaco respectively, for a combined €56million (£48.6m, $58.6m).

“There is a pathway for all AZ youth players and they can see our track record over the years,” said Brandenburg in 2020.

Kerkez and Reijnders are examples of AZ’s recruitment in older academy age groups. Both were signed as teenagers and became key first-team players, then were sold to Bournemouth and AC Milan respectively this summer for more than €37million combined.

AZ staff have explicitly spoken of trying to have half their first-team squad made up of graduates from the club’s academy, while also aiming for a top-three league finish and being competitive at European level.

First-team head coach Pascal Jansen has been in charge since December 2020, the third longest-serving boss in the 18-team division behind Rotterdam side Excelsior’s Marinus Dijkhuizen and Rogier Meijer of Nijmegen’s NEC.

Jansen, who became the youngest ever Pro License coach at 35, was promoted from assistant head coach when Arne Slot was fired after secretly entering negotiations to join Feyenoord.

Over almost three years, he has cemented the academy-to-first-team pathway: this is AZ’s sixth consecutive season with a squad average age of under 25, Jansen has given 30 players their senior debuts while aged 22 or younger, in the Eredivisie or Conference League, including seven of that Youth League-winning squad.

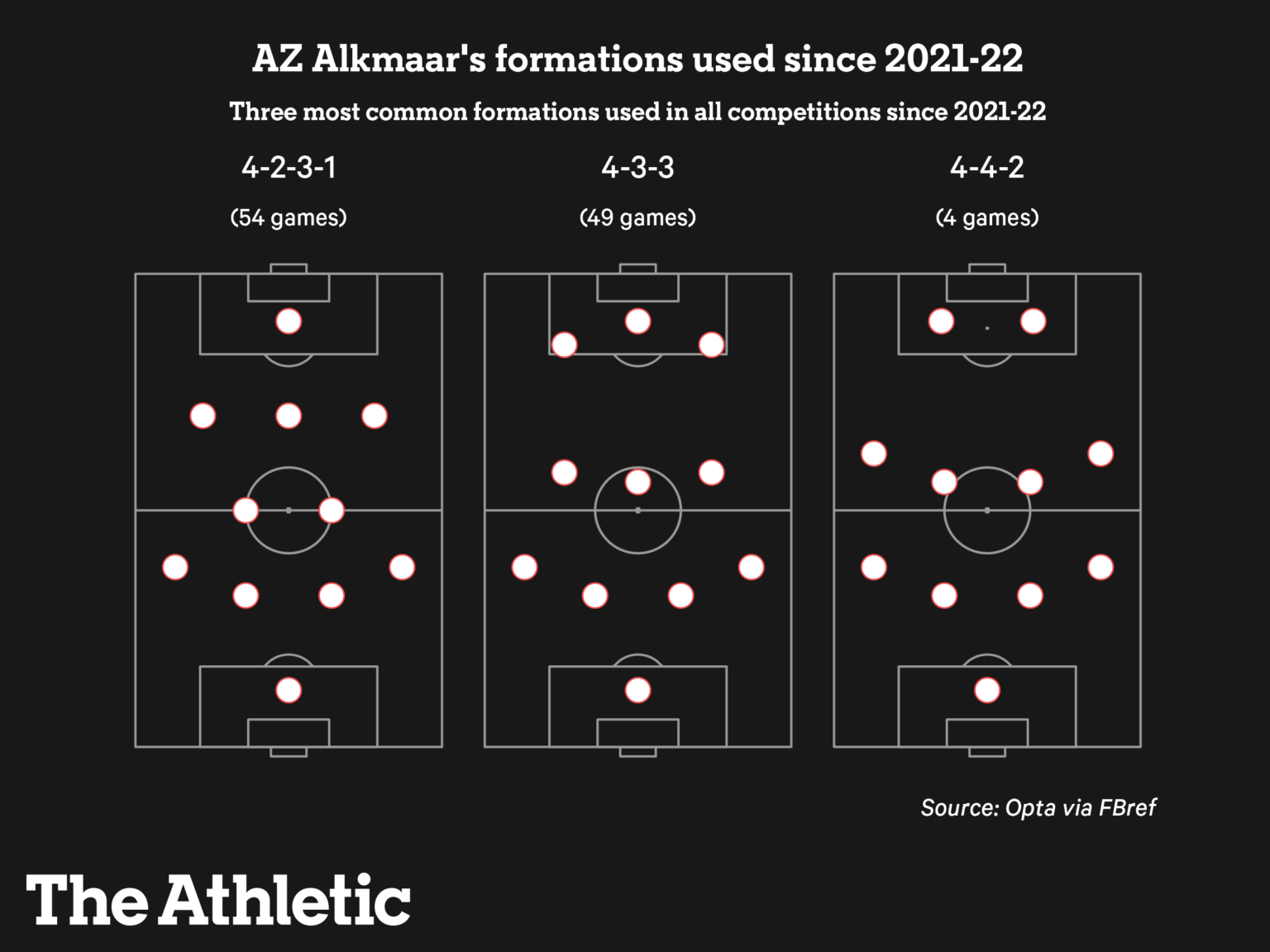

Systematically, he plays the quintessential Dutch 4-3-3 and there is a top-down philosophy which runs from the first team into the academy.

“My ideas connect so well with AZ,” Jansen said in 2021. “When I close my eyes and see my team perform, it is about pressing, it is about being dominant, being disciplined but with room for creativity.”

It is no wonder so many academy players continue to move to AZ from across Europe.

Tournaments are won as a team but AZ have some exciting individuals.

Starting from the back, 19-year-old goalkeeper Rome Jayden Owusu-Oduro has all the makings of a modern No 1.

He kept five clean sheets in the Youth League last season, the most of any goalkeeper, and starred with reaction saves against Real Madrid and Barcelona, with neither side scoring past him. Owusu-Oduro, who was born in the Netherlands but holds Ghanaian citizenship, saved two penalties in their semi-final shootout win over Sporting, and has featured on the bench for the first team.

Mexx Meerdink, a tall No 9, was the talisman and captain.

His timing of runs and positioning in the box were beyond his years, netting a mix of poached finishes from rebounds, one-touch finishes from crosses and goals off through balls, too. Meerdink, now 20, netted the final two goals in the final against Hadjuk to finish joint-top scorer (nine) with Panathinaikos’ Bilal Mazhar. He was the first player since Barcelona’s Munir El-Haddadi in 2013-14 to finish top scorer and win the competition.

Left-winger Ernest Poku and right-winger Jayden Addai, both playing inverted, complemented Meerdink perfectly.

The pair were incisive and varied one-v-one, as capable of combining with one-twos as they were dribblers, often cutting inside and attacking defenders on the outside. Both have excellent ball-striking techniques. Poku, now 19, ended the 2022-23 tournament with 10 goal involvements (eight goals, two assists) and Addai, who only turned 18 this August, had seven (four goals, three assists).

AZ’s five goals in the final were shared between Meerdink, Addai and Poku.

AZ’s approach to coaching goes against convention.

Coaches work across age groups — for instance, the under-18s’ coach may assist with the under-12s. The thinking is that if they can understand the principles with one age group, particularly the younger ones, they are aware of how it fits into the broader picture.

It is a conscious effort to avoid confirmation bias — seeing what you want to see — as having more eyes on the same players means coaches can cross-reference opinions, which, when coupled with their technical/tactical/psychological analysis of a player, provides a richer understanding.

“Every training session should be surprising, so we try to change the circumstances to challenge our players,” said Brandenburg in 2020. “Changing up the surface is one way of doing that, because every surface requires a different technique. We also like to change the size of the ball.”

Academics have termed this ‘planned disruptions’, a method of training players to adapt under pressure and develop coping strategies. Beuker calls them “sh**ty situations, where they have to struggle and compete to show if they are willing to learn and to suffer.” At AZ’s training ground, which was built in 2016, there are grass, sand and asphalt surfaces.

They change formations too, all with the intention of developing creative, problem-solving players, who are able to take technical and tactical agency.

AZ’s tactical adaptability underpinned their success in the Youth League. Their knockout-phase wins against Barcelona and Real Madrid were defence-first performances, with clinical counter-attacking. They had 35 per cent possession in both games but only conceded two big chances, creating eight.

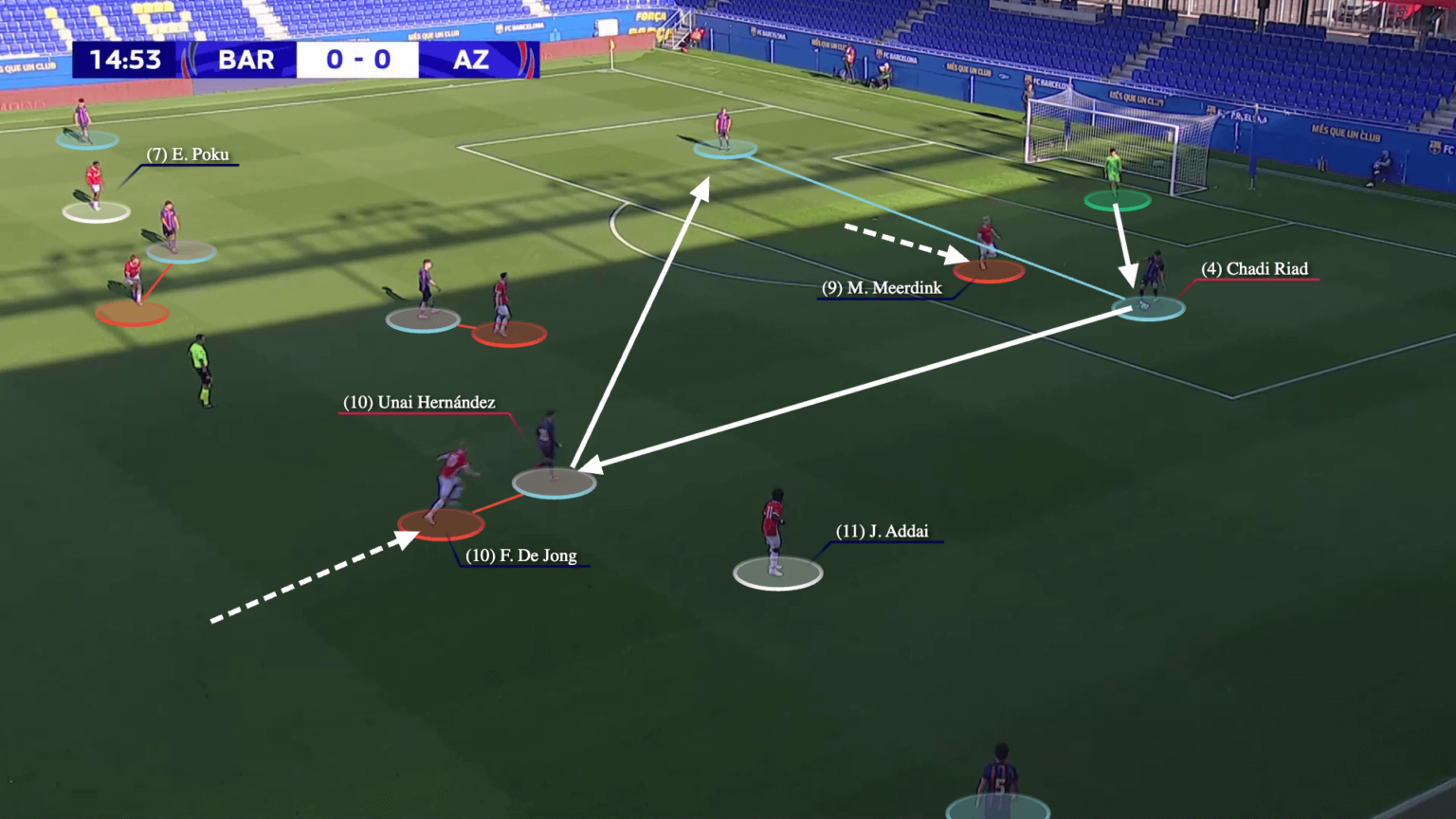

Away to Barcelona in the round of 16, they largely defended in a 4-4-1-1 shape, dropping No 9 Meerdink and No 10 Fedde de Jong close to Barca’s deepest midfielder (yellow dot). As Barcelona attacked in a 4-3-3, AZ’s central midfielders man-marked and the wingers stayed deep to press the home side’s full-backs.

But they mixed in plenty of high pressing, keeping that man-for-man system centrally, forcing Barcelona to go direct. It was not perfect — on a couple of occasions they were played through — but they consistently disrupted Barca’s build-up, and only conceded three shots (13 faced total) from outside the box.

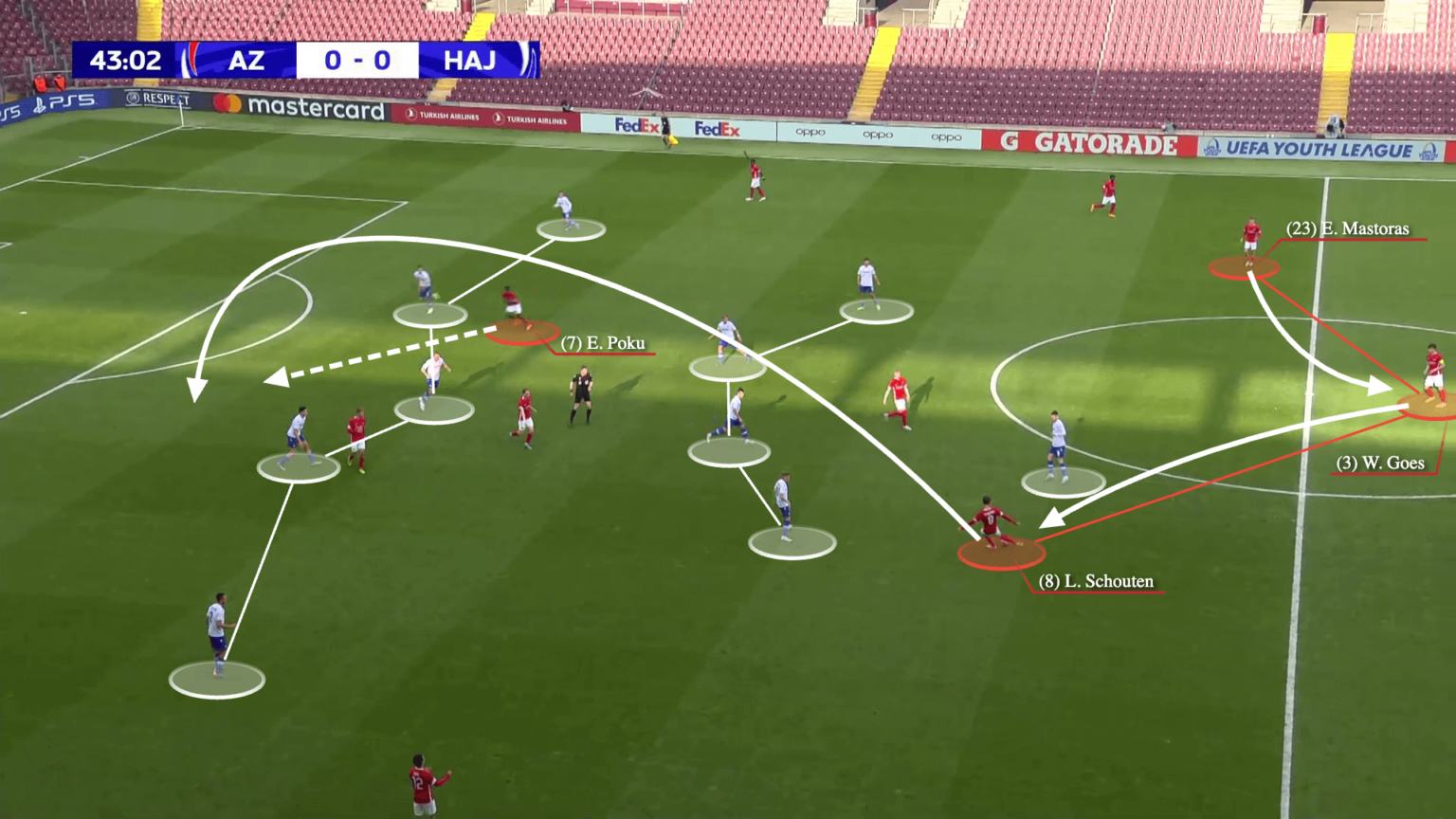

In the final against Croatia’s Hajduk, AZ had more than 65 per cent possession, registered five big chances without conceding any, had more high turnovers (eight versus five) and won the shot count 16-5.

Centre-back Wouter Goes epitomises the player that AZ try to create — tactical, thoughtful but unique. Before that final in Geneva, Goes spoke about the game having “more pressure” but being a “totally different match” than the semi-final in the same Swiss city three days earlier: “Sporting pressed really high but Hadjuk will play deeper. We need to keep possession.” They switched to a back three against Hajduk’s 5-4-1, in part due to centre-back Finn Stam having been sent off against Sporting. They were without Meerdink for the first half, as he only flew in on the morning of the match after playing 70 minutes for AZ’s first team in the Eredivisie the day before. Central midfielder Lewis Schouten, a right footer, filled in at left centre-back and had the most touches (122) and successful passes (94, from 109 attempts). He completed 15 of his 24 long passes, with AZ trying to go over Hajduk’s compact block. One such pass found Poku in-behind, who was fouled for and then converted a penalty to open the scoring just before half-time.

The balances of power have, and are shifting in the Eredivisie.

Last season Feyenoord won the league, meaning the title did not go to Amsterdam for the first time since 2017-18 (albeit there were no champions in 2019-20 because of the pandemic-enforced voiding of the season), when PSV won it ahead of Ajax and third-placed AZ.

Ajax are a club in implosion, having made their worst start to a season since 1964 after once again selling multiple key players in the summer. Feyenoord have to juggle a Champions League group pitting them against Celtic, Atletico Madrid and Lazio with defending their title. With four second-place finishes in the past five seasons, PSV look genuine title contenders this time.

But never look past AZ. Not their past generations and especially not this one.